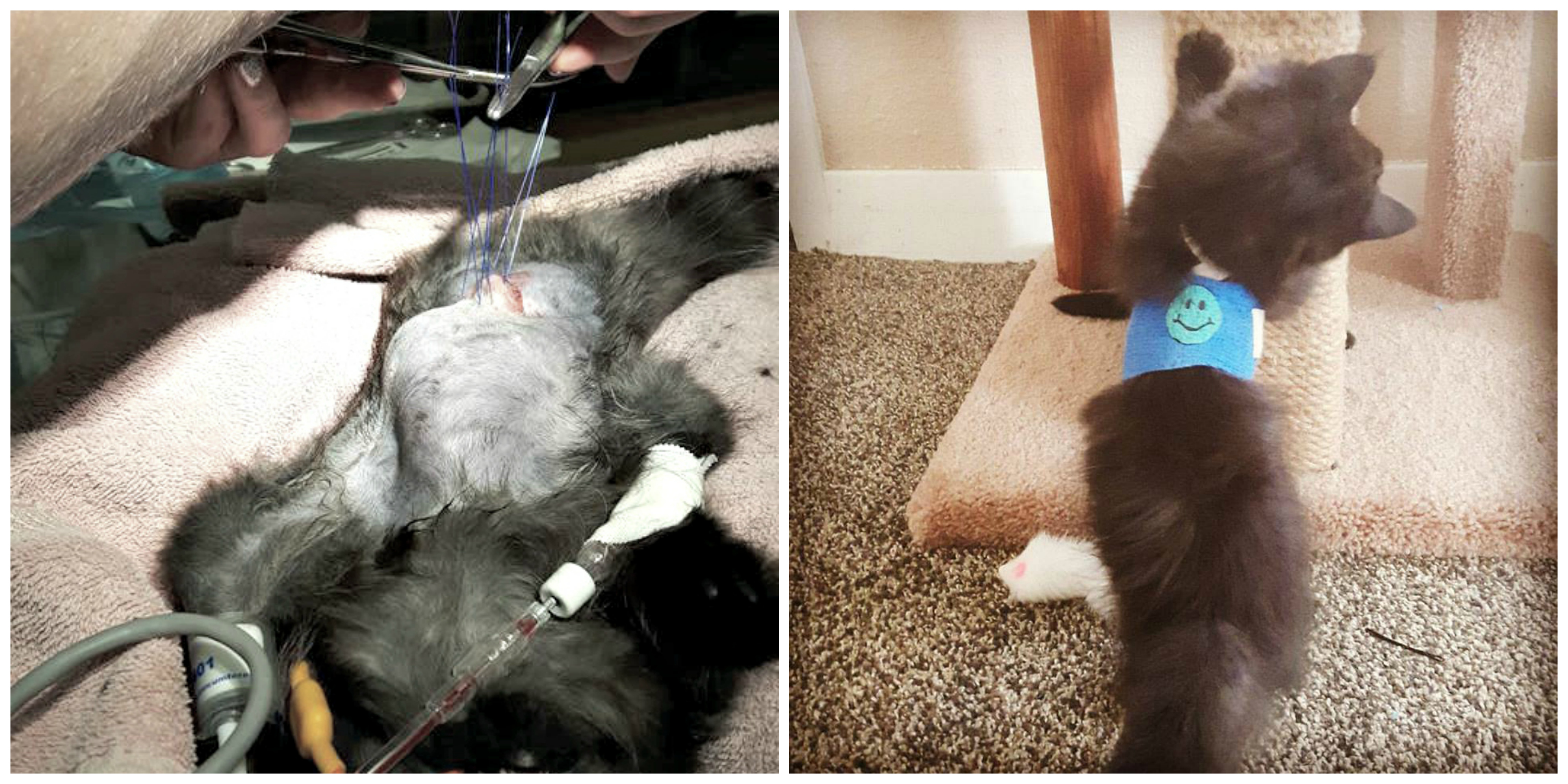

Appropriate pain control after this little kitten’s chest surgery meant a quick start on physical therapy and a fast return to health!

There’s a running joke in veterinary medicine that our job is harder than human medicine for two reasons, one: that we’re required to treat more than one species and two: that our patients can’t talk to us. While I have no interest in restarting the ‘who has it worse’ argument (especially with close family members who work in human medicine!) I do want to address one of the most difficult parts of veterinary medicine: the where does it hurt conundrum. How do you identify and treat pain in an animal which can’t tell you how much pain it’s in or even why?

Human medicine uses a person’s pain as a diagnostic tool all the time. Every one of us has probably been asked, at one time or another, to describe our pain to a health care provider. How badly does it hurt on a scale of one to ten? Is it sharp and stabbing or dull and aching? Does it come and go or stay steady? Does it get worse when I press here? These questions can tell the difference between a broken bone and a sprained muscle, stomach cramps and acute appendicitis, gastric reflux or a heart attack. Veterinary medicine doesn’t have that luxury. Instead we’re forced to rely on our patient’s behavior, vocalizations, and reports from their owners who in many cases will see far more than we will.

Animals will instinctively hide their pain. This is a survival mechanism which has kept species alive and thriving for hundreds and thousands of years, but unfortunately it’s a survival mechanism tailored to a world without veterinarians. The less domesticated the animal is the better they are; birds in particular are notorious for appearing completely healthy right up until the moment they drop dead. Even within species different breeds have reputations – working/guardian breeds and pit bull type crosses tend to be incredibly stoic while toy breeds (and, strangely enough, heeler-types) tend to be much more reactive and inclined to dramatics. But every animal is different, and no two pets are going to give you the same indications of pain.

An example: two dogs who were both presented for lameness evalutaions. One was non-weight-bearing and screamed whenever the owner attempted to examine the limb in question, while the other was sore and had an obvious limp but was weight-bearing, eating/drinking, and seemed completely normal otherwise. The first dog was found to have a dewclaw that had grown into the side of the paw; the trimming of the dewclaw and the administration of some pain medication resulted in it walking out of the clinic without the slightest hint of soreness. The second dog had x-rays which revealed a nasty fracture, requiring an extensive orthopedic surgery to repair followed by months of healing. If you were to show me a video clip of the two animals walking side-by-side, I would have for sure thought that the first dog was the one with the break.

So what does this mean for us and for you as an owner? It means, first and foremost, that it’s our duty and our responsibility to your pets to conduct a thorough physical exam on all of our patients and to do diagnostic tests where appropriate. We appreciate the costs of veterinary medicine – oh believe me and my current bank account balance, we do – but without the ability to ask your dog where it hurts, we need to rule out serious injury and illness. In the example above it was clear after a basic exam that the femur was damaged and x-rays were performed to determine the extent of the fracture, but that’s not always the case. I’ve seen a pet brought in for coughing and chest radiographs revealed not only the severe bronchopneumonia which had caused the coughing, but also broken ribs which were undoubtedly extremely painful and which might not have been identified otherwise. When we suggest radiographs, ultrasounds, or bloodwork, it’s because we’re concerned about something that we can’t rule in or out based only on our exam, and because it’s our duty to make sure that your pet isn’t living in pain or discomfort. We also need to perform diagnostic bloodwork on animals who take regular pain control for chronic conditions such as arthritis to make sure that their body is able to handle the medication (NSAIDS such as Metacam/meloxicam in particular are excellent front-line meds for pain control but can have long-term side effects such as kidney disease) and that adjustments don’t need to be made to the dosage for your pet’s welfare.

Secondly, it means that we have an obligation to provide appropriate pain control. A human can be asked “How is your pain?” and be given more or less pain control based on their response. An animal must be closely assessed for signs that they’re uncomfortable, from the obvious (limping, crying out, not eating/drinking, guarding a limb) to the incredibly subtle (squinting, facial ‘tightness’, certain sleeping or sitting positions, chewing more on one side than another, slight variations in normal routine). This can be extra difficult in hospitalized patients who are frequently stressed out and confused anyway by the change in scenery, or animals which have recently been anesthetized and may be dysphoric (frantic and confused) from the drugs. When in doubt, we tend to assume pain; better to be not painful and receive drugs than to be painful and not be treated for it. Pain causes delayed healing and frequently leads to complications as well as negative behavioral changes.

We can’t ask your pet where it hurts, but we still need to find out where and why. And once we know the reason, we need to be able to take that pain away. It can be tempting to say things like “He needs to rest the leg and if it doesn’t hurt he’ll just want to run on it”, but please consider yourself in your pet’s place. If you just had major abdominal surgery (spays), had your testicles removed (neuters), a deep gash repaired with internal and external sutures, a broken limb, or major trauma from a car crash, I can guarantee you’d be asking for meds. Your pet may not be able to form the words and may not even be comfortable enough expressing their discomfort through body language, but I can just as easily guarantee you that they’re hurting too. Say yes to pain control and you’ll be saying yes to a happier, healthier pet much more quickly!

2 comments

This should be required reading for ALL pet owners. Thanks for putting that into easy to understand terms.

Thanks, Rob! You are more than welcome to share among your clinic and clients 🙂